lying-before-us

What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.

There was an odd passage in a woodworking memoir I read because I was taking the long way ’round in trying to think about craftsmanship. The woodworker had been commissioned to make a cabinet or an armoire or something large and bulky and expensive. He made it in his shop and it was beautiful and perfect and just what the client wanted. When the piece was delivered to the client and placed in the room for which it had been built, it wobbled slightly, as though it wasn’t quite square. The client was upset. The woodworker was indignant: it was not his fault that the client’s house was not level. 1

When I first wanted to learn how to knit, I purchased a hank of linen yarn. Not knowing any better, I took it home and tried to wind it into a ball, but the initial result was a snarled tangle. Without a swift or winder, this was to be expected. 2 I didn’t know what those tools were, then, and also didn’t know that the yarn could be wound at the store, if one asked. It took a long time to sort out the mess. Had the yarn been less expensive or my interest less keen, I would have discarded the lot. Indeed, years later I am still surprised I spent the time to untangle it.

The unconditional character of faith, and the problematic character of thinking, are two spheres separated by an abyss.

For months I would look at the book on the shelf and amuse myself with the title: what is called thinking? what is called thinking? what is called thinking? what is called thinking? This game provoked such a degree of annoyance that there was nothing to be done but read the book. Reading the book resolved neither the annoyance nor the ambiguity.

As I read, I worried, which is not my custom – though I suppose worrying is a sort of cousin to thinking. I was worried, not because I was not concerned with thinking, but because it seemed that thinking was not the concern of the book. Rather, the book seemed to me rather to concern power and the authority to say that this is what thinking entails or could entail or should entail or might entail, if only one had begun to try to think about it. 3 Yet for whom is one abrogating the right to decide what thinking is? It is a troubling question, because one of the first thing one notices is that ‘[s]omething is missing from his life and his work […] One could call this missing element “humanity”, in several senses.’ 4 Not all of the charming metaphors, not all of the cabinetry dovetailed into the argument can draw the eye away from this abyss: why should one have faith in this person’s notions about thinking?

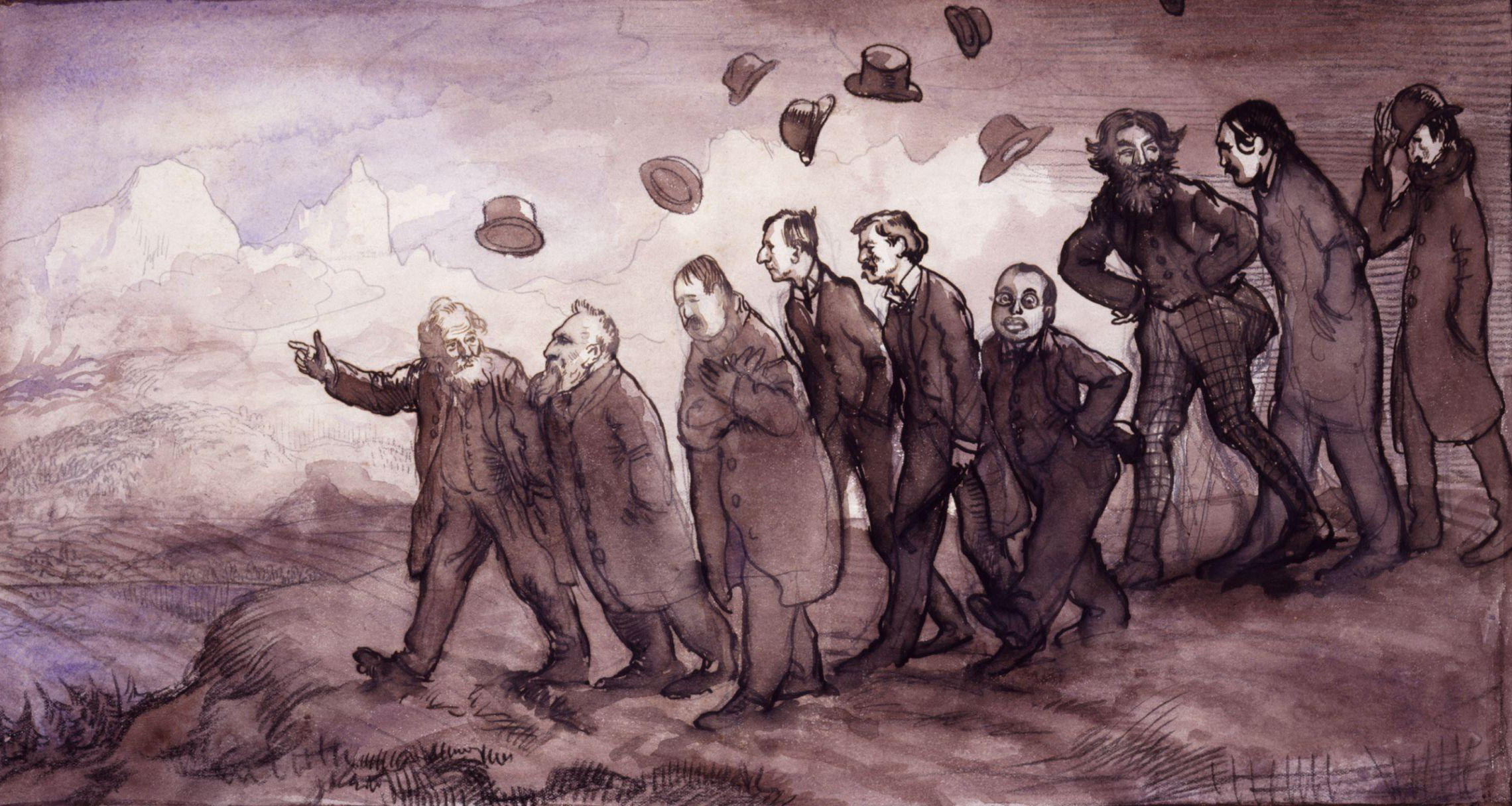

Curiously, it reminds me of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement – attempting to look forward while facing the past, or vice versa. There is the same sense of wearing a mask or playing a part. There is the same sense of precariousness, that each step must be chosen with care, as in a minefield, as in a labyrinth. There is the same sense of something hidden.

What is the purpose of a cabinet commissioned from a woodworker? To adorn the woodworker’s shop? No – it is twofold: to furnish the room of the person who commissioned it and to pay the way of the woodworker. And if it does not suit the room, who then is to blame? Perhaps it is the taste of the buyer, perhaps the faulty craftsmanship of the woodworker, perhaps the nature of the material itself, which is subject to too many atmospheric conditions to ever exist as envisioned in the material world.

For what purpose does one untangle the yarn? To have untangled yarn? No: to make some other thing that requires the yarn to be in a state of not being tangled, but for which untangling is not a prerequisite. Indeed, untangling is not necessary, if the yarn had been treated as intended, as knowledge or experience would dictate, not as ignorance would presume.

And still, we are not thinking.

- I don’t remember much else about the book except the bits about hiking and/or rock climbing.[↩]

- My experience was not novel; one doesn’t often think about what a nuisance string can be. One sees Ariadne in a new light, as a bit of a troublemaker.[↩]

- An entail is always so alienating for one outside its boundaries – one thinks of Mr. Collins.[↩]

- Sarah Bakewell, At the Existentialist Café (New York: Other Press, 2016), p. 320, see also pp. 50–97, 175–195. As is well known, Heidegger was not particularly nice; whether he can be forgiven is a question that calls for minds other than mine. A potted summary of Heidegger’s philosophy can be found elsewhere.[↩]