February 2015

in the study

3 February 2015, around 5.22.

Curie

of the laboratory

of vocabulary

she crushed

the tonnage

of consciousness

congealed to phrases

to extract

a radium of the word

What is the use of a violent kind of delightfulness if there is no pleasure in not getting tired of it. The question does not come before there is a quotation. In any kind of place there is a top to covering and it is a pleasure at any rate there is some venturing in refusing to believe nonsense. It shows what use there is in a whole piece if one uses it and it is extreme and very likely the little things could be dearer but in any case there is a bargain and if there is the best thing to do is to take it away and wear it and then be reckless be reckless and resolved on returning gratitude.

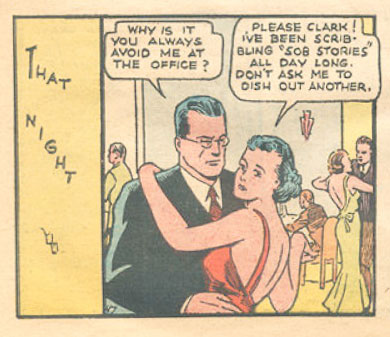

sob stories

5 February 2015, around 9.31.

Anna Halsey was about two hundred and forty pounds of middle-aged putty-faced woman in a black tailor-made suit. Her eyes were shiny black shoe buttons, her cheeks were as soft as suet and about the same color. She was sitting behind a black glass desk that looked like Napoleon’s tomb and she was smoking a cigarette in a black holder that was not quite as long as a rolled umbrella. She said: ‘I need a man.‘

I watched her shake ash from the cigarette to the shiny top of the desk where flakes of it curled and crawled in the draft from an open window.

‘I need a man good-looking enough to pick up a dame who has a sense of class, but he’s got to be tough enough to swap punches with a power shovel. I need a guy who can act like a bar lizard and backchat like Fred Allen, only better, and get hit on the head with a beer truck and think some cutie in the leg-line topped him with a breadstick.’

‘It’s a cinch,’ I said. ‘You need the New York Yankees, Robert Donat, and the Yacht Club Boys.’

Montaigne 1.4

6 February 2015, around 14.33.

But, in good sooth, when the hand is raised to strike we feel hurt if it misses its aim and falls on empty air; so also, if the sight is to have a pleasant prospect, it must not be lost and scattered on vacant space, but have an object to sustain it at a reasonable distance […] so it would seem as if the soul, when moved and shaken, were lost in itself if it is given no hold; it must always be provided with an object to aim at and work upon.

A charming truism, this essay, that one tends to lash out at something if one hurts, even if one cannot attack the cause of the pain – and this can in fact be counterproductive. Thus the case of the gouty man who persists in eating rich foods against his doctor’s orders so that he has the comfort of feeling that he knows the cause of his pain – ‘that if he could shout and curse the Bologna sausage, or the ham, or the ox-tongues, he felt very much better’.

a wholesome note of doubt

8 February 2015, around 9.16.

When we had all read the portion of the serial story, and very definitely not before, we discussed endlessly at tea-time how the characters would turn out and who would marry whom. With so little new reading-matter to distract us we were able to carry all the details in our head until the next issue. The plot seems simple as I look back on it: a girl was engaged to a man whom duty bade her marry, while she was really in love with another. No one in those stories was ever actually married to the wrong man. To me the triangle seemed insoluble, and I was all prepared for a broken heart and tears. But Charles announced one day that the first young man would die, and all would be well. ‘How do you know?’ we asked him. ‘I noticed him cough in the second chapter.’

whirlwind

9 February 2015, around 10.38.

She had been on the fringe of the class called educated, with a mind sufficiently at leisure to enjoy noticing things, and speculating over them, and reading books from the public library in order to learn more exactly about them. But this was a long time ago, and the scraps of knowledge she had then accumulated lay like a heap of dead leaves, broomed away into an unfrequented corner of her mind and only stirring now and then, and only the lightest and least significant of them stirring, at that.

Montaigne 1.5

13 February 2015, around 10.11.

As to ourselves, who, not being so overscrupulous, give the honour of the war to him who has the profit of it, and who say, with Lysander, that ‘when the lion’s skin is too short, we must eke it out with a bit from that of the fox’, the most usual occasions of surprise are derived from this exercise of cunning; and there is no moment, we say, when a chief should be more wide-awake, than that of parleys and treaties of accomodation.

Crambe repetita (35)

15 February 2015, around 5.21.

At home he had an unpleasant surprise. In the dining room his ten-year-old son was studiously learning the alphabet.

Terenty tore the book out of the boy’s hands and ripped it to shreds.

‘You mangy pup!’ he yelled. ‘So you thought you’d start readin’ books, eh? Learn the sciences, eh? So you wanna end up a goatherd?’

Angrily banging the door behind him, he went to his study to eat cabbage soup.

The little boy sobbed and sobbed as he gathered up the shredded pages. The lady-doctor cleared the dishes away, tiptoed up to the crying boy, and tentatively stroking his head, she whispered, ‘Don’t cry, my child. One day we shall see the heavens glittering like diamonds.’

Montaigne 1.6

20 February 2015, around 9.40.

- The dangers of conferring with the ‘enemy’ – both if one goes on one’s own or with one’s cohorts: dangers on all sides. 1

- Circumstances create their own consequence, and lead naturally to a certain course of action; the refrain from that action becomes difficult (specifically to do with the difficulty in restraining a conquering army from looting a city, even if pledged not to do so, but there are of course other applications).

- ‘But the gods avenged this subtle perfidy’ – and – ‘they who run a race should use their best speed, but by no means are they at liberty to lay a hand on their adversary to stop him, or to stretch out a leg to trip him up’ (says Chrysippus).

- A fault of humanism, to remove the might of divine disapproval: so inconvenient.[↩]

regression analysis

21 February 2015, around 17.51.

One of the more interesting stylistic problems during the Hellenistic period was the problem of quotation. The forms of direct, half-hidden and completely hidden quoting were endlessly varied, as were the forms for framing quotations by a context, forms of intonational quotation marks, varying degrees of alienation or assimilation of another’s quoted word. And here the problem frequently arises: is the author quoting with reverence or on the contrary with irony, with a smirk? Double entendre as regards the other’s word was often deliberate.

The relationship to another’s word was equally complex and ambiguous in the Middle Ages. The role of the other’s word was enormous at that time: there were quotations that were openly and reverently emphasized as such, or that were half-hidden, completely hidden, half-conscious, unconscious, correct, intentionally distorted, unintentionally distorted, deliberately reinterpreted and so forth. The boundary lines between someone else’s speech and one’s own speech were flexible, ambiguous, often deliberately distorted and confused. Certain types of texts were constructed like mosaics out of the texts of others.

Montaigne 1.7

27 February 2015, around 16.49.

It is perhaps the result of reading too many detective stories, but Montaigne’s notes on the importance of intentions was full of possibilities:

They do still worse who reserve for their last will the declaration of some spiteful intention against a neighbour after having concealed it during life; thereby manifesting little regard for their own honour, since they irritate the offended against their memory, and less for their conscience, not having been able, even out of respect to death itself, to let their ill-will die down, but extending the life of their hatred beyond their own. Unjust judges, who defer judgement to a time when the case is beyond their jurisdiction!