February 2021

biblidion

5 February 2021, around 15.06.

The other morning I happened to finish reading a relatively recent translation of The Encheiridion by Epictetus (well, via Arrian), which is a text I almost always find to be a tonic (if not taken in excess). In addition to soothing my temper, though, the present reading also left me somewhat unsettled, not with the text and its ideas, but with the little book itself. Its intended market (i.e., why in fact it was published in its present manner) was not entirely clear to me: in design – veneered erudition or self-help for the board/bored room 1 – it appears like the sort of thing one might include in an office white elephant exchange, but given its content, that would be an impressive level of snark from either a boss (‘Your job is to put on a splendid performance in the role you have been given, but selecting the role is the job of someone else’ [17]) or an employee (‘it is enough if each person performs his own job’ [24]). It is also not informative enough for a textbook, nor sufficiently grounded for the general reader. As one blurb sagely observes: ‘There really isn’t anything else out there quite like this book.’

There were numerous places (beyond that included on the erratum) where the value of and need for a proofreader were apparent. The inclusion of the Greek text (the same as that used in the Loeb) was particularly perplexing (again, for whom is this book intended?) and led to several infelicities of design (blank pages, awkward white space for the translation to catch up, etc.). It feels odd to comment on such things, however, when Epictetus would advise that they are not under the reader’s control and therefore not something about which a reader should feel disquiet: say rather that the principles of typographic elegance have been returned, and the skills of the proofreader called back to their maker (cf.).

- Part of the ‘Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers’ series.[↩]

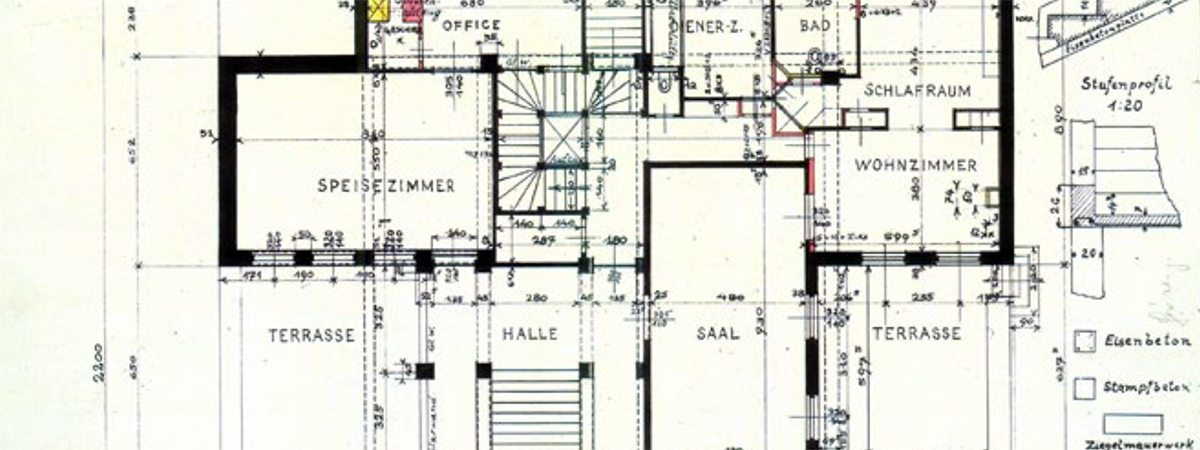

arche-tecton

10 February 2021, around 5.08.

There is a passage in the third chapter of Toril Moi’s Revolution of the Ordinary: Literary Studies after Wittgeinstein, Austin, and Cavell that drew my eye:

In many cases, then it is useless to spend time and energy trying to produce a sharp concept. To avoid meaningless work, we need to understand the situation we are dealing with. If I want to take a picture of you in front of the Eiffel Tower, surely “stand roughly there” is all I need to say. I could get out the satellite navigation system and geocode your position, but unless there is some reason why I must take a picture of you on an exact spot defined by longitude and latitude, it would be pointless to go to so much trouble. (73)

This follows a section supporting a Wittgensteinian antipathy to unnecessary hair-splitting (after a particularly deprecating account of Derrida’s aversion to either prevarication or periphrasis – I wasn’t paying particularly close attention, so I cannot quite recall). 1 Moi takes the opportunity to observe that Wittgenstein trained as an engineer, which I believe was intended to provide credentials for his attention to precise meaning/details/concepts as opposed to general ones – that is, his ability to engage in a sharp focus rather than a blurry (or merely evocative) one.

This led me to think of the house that Wittgenstein collaborated in designing for his sister in Vienna, 2 and the philosopher’s command, when construction was nearly complete, for the builders to raise the ceiling by 3 cm to match the proportions he desired. I remember reading about the incident somewhere that compared the privileged dilettante-ism that could make such a demand with the necessary bowing to cost and material reality that would characterize someone who had to make such choices on a regular basis (i.e. a professional, such as Adolf Loos or Paul Engelmann).

That is all by the way. What I meant to say is that, if one wants to take a picture of an acquaintance in front of the Eiffel Tower, 3 ‘stand roughly there’ would certainly be sufficient guidance – if one happens to be at all near the structure in question. This is a rather big assumption to make for grounding the example. What if one happens to be in Las Vegas? Would a photograph before an ersatz tour Eiffel have the same meaning? Would it matter? 4

- NB, my (mis)characterization here is, as you will have guessed, ὦ σοφώτατε σύ, wryly ironical.[↩]

- It had beautiful radiators, but appears not to have been entirely home-like; indeed, one of Wittgenstein’s sisters (not the one for whom the house was built) said: ‘It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods than for a small mortal like me, and at first I even had to overcome a faint inner opposition to this “house embodied logic” as I called it, to this perfection and monumentality.’[↩]

- Although why one should wish to do so escapes my understanding.[↩]

- I am not actually disagreeing with Moi. This is just the sort of whimsical nonsense that always springs up while I am reading.[↩]

12.ii.2021

12 February 2021, around 6.24.

‘They were old maids. They weren’t cranky because they hadn’t had a man but because they’d had too many old books.’ —the gravedigger, qtd. in Ronald Blythe, Akenfield

moonlit folly

14 February 2021, around 5.38.

In childhood, when we fall on the ground we are disappointed that it is hard and hurts us. When we are older we expect a less obvious but perhaps more extravagant impossibility in demanding that there should be a correspondence between our lives and their setting; it seems to all women, and to many men, that destiny should at least once in their lives place them in a moonlit forest glade and send them love to match its beauty. In time we have to accept it that the ground does not care whether we break our noses on it, and that a moonlit forest glade is as often as not empty of anything but moonlight, and we solace ourselves with the love that is the fruit of sober judgment, and the flower of perfectly harmonious chance. We even forget what we were once foolish enough to desire.

16.ii.2021

16 February 2021, around 11.50.

‘Think in moderation. Remain on your bed. Contemplate on the wall the daylight vanishing, and the balance of light and shadow pursuing one another insensibly towards the night. Simple time is a great remedy.’ —Paul Valéry, Dialogues (trans. W.M. Stewart)

16.ii.2021

16 February 2021, around 12.00.

‘Unravel me that miserable mixture of equivalent sensations, of memories without employment, dreams without credit, conjectures without consistency…Summon and rally all those little unfocused forces which are adrift in your fatigue. Your weakness is simply their confusion.’ —Paul Valéry, Dialogues (trans. W.M. Stewart)

the guest-room bookshelf

19 February 2021, around 14.22.

So many books enter one’s life through happenstance, rather than through the ordered chaos of book reviews or bibliographies or the propinquity of a library or bookstore shelf (each good in its way). 1 This aleatoric approach to book selection is something I associate with travelling, and I like to think of it as the guest-room bookshelf effect: these are the books abandoned in hostels, left on a free shelf, or consigned (with other unfavored items that one would not want to discard) to a guest room. These are books that have been worn out, outgrown, or gone astray – the jetsam (usually, but also the flotsam) of an unknown reading life. Books I have discovered in this way include:

- Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

- Martin Amis, Koba the Dread

- Peter S. Beagle, I See by My Outfit

- A.S. Byatt, Babel Tower

- Edna Ferber, Giant

- Ivan Illich, Shadow Work

- Kate Jacobs, The Friday Night Knitting Club

- Carlo Levi, Christ Stopped at Eboli

- Nancy Mitford, Frederick the Great

- Caryl Phillips, The Atlantic Sound

- J.F. Powers, Morte d’Urban

- Barbara Pym, Quartet in Autumn

- Antonio Tabucchi, Requiem: A Hallucination

- Unni Wikan, Behind the Veil in Arabia: Women in Oman

My initial thought had been to make up a list of books that I would want to include in a guest room, the sort of things that might spur the kind of reading I particularly had in mind – the unexpected, the not-too-strenuous, occasionally the not particularly great, but often the only thing available with all of its pages in a language one understands. I realized, as I thought about it, that none of the books I would choose for a guest room would be the sort of book I would like to encounter there. 2 This was perhaps to be expected, so it was without regret that I set aside the project of furnishing an imaginary guest room with an imaginary library.

- Thrift-store bookshelves come close, though.[↩]

- Most of the books on the list I have completely forgotten about; whether or not that is a recommendation, I leave to the reader to determine.[↩]

18.ii.2021

20 February 2021, around 7.40.

‘And it is not worth the trouble of thinking of philosophy; all the more horoscopes! – more than spider-webs in a ruined castle.’ —Hamann, Aesthetica in nuce (trans. Kenneth Haynes)

coxcombry

22 February 2021, around 12.30.

I remember reading something about a chatterbox in a coach who left himself open to some devastating wit by asking his fellow passengers if he wasn’t a coxcomb and I have no idea where I read it but it was about a sixth of the way down a verso. I think.

The witticism involved repeating the coxcomb’s statement to a fellow passenger who was hard of hearing.

This might be like that book with a green cover that I will never be able to find.

I think it was Boswell. Or Boswell adjacent. But I can’t find it.

It could also be a historical novel I didn’t finish reading, though.

The only thing I am actually certain about is the use of the word ‘coxcomb’.

And if ‘coxcomb’ were included as an index entry to Boswell, it would state ‘passim’.

(This is not wholly because of Boswell, mind.)

24.ii.2021

24 February 2021, around 17.25.

‘What would all knowledge of the present be without a divine remembrance of the past, and without an even more fortunate intimation of the future, as Socrates owed to his daemon?’ —Johann Georg Hamann, A flying letter to nobody, the well known (trans. K. Haynes)

human kindness, curdled

25 February 2021, around 5.23.

‘A plan of the cities of London and Westminster’, etc., by Johns Roque, Pine, and Pinney (ca. 1746)

We disputed about some poems. Sheridan said that a man should not be a poet except he were excellent; for that to be a mediocris poeta was but a poor thing. I said I differed from him. For the greatest part of those who read poetry have a mediocre taste; consequently one may please a great many. Besides, to write poems is very agreeable, and one has always people enough to call them good; so that a man of a tolerable genius rather gains than loses.

Dialogue in the Sitting Room

PF. If you don’t like Boswell, why would you waste your time reading his diaries?

MFC. One learns so much in the encounter, and time spent in learning is never wasted.

PF. Huh. Are there any muffins left?

Before I started reading Boswell’s London Journal, I knew it would irritate me. I’m not quite sure why I picked it up. Byron’s letters I got because I started reading them in the library (remember going to the library?) and was so tickled by them I purchased a copy to read at my leisure. Part of me wants to believe something similar happened with Boswell, but I suspect I was at the large and local bookstore, browsing the B section in the blue room, and saw a copy with a ratty dust wrapper and was amused. I was ready to be irritated, too, which is a good way to approach a writer with a prickly personality. No reader approaching Boswell in this way will be disappointed.

Her marrying him was just to support herself and her sisters; and yet to a woman of delicacy, poverty is better than sacrificing her person to a greasy, rotten, nauseous carcass and a narrow vulgar soul. Surely she who does that cannot properly be called a woman of virtue. She certainly wants feeling who can submit to the loathed embraces of a monster. She appear to me unclean: as I said to Miss Dempster, like a dirty table-cloth. I am sure no man can have the gentle passion of love for so defiled a person as hers — O my stomach rises at it!

Dialogue on the Stairway

MFC. He’s just so self-centered. He never acknowledges his privilege and is always complaining that no one does him any favors. He has no sympathy for what other people feel or think. He never stops to consider the limited opportunities available to others – especially women – but is entirely wrapped up in the confines of his own perspective.

PF. It’s Boswell’s diary. What did you expect?

When a man is out of humour, he thinks he will vex the world by keeping away from it, and that he will be greatly pitied; whereas in truth the world are too busy about themselves to think of him, and ‘out of sight, out of mind.’

If there is something to be said for allowing oneself to be irritated by one’s reading, there is also a point at which one must decide to forgo the dubious pleasure. 2 After the last conversation (mentioned above), I was forced to acknowledge that my irritation with Boswell was a piece of affectation: I had decided to be irritated and so construed everything in the worst possible way. The London Journal is an amusing, charming piece of work. While I might personally prefer to read Boswell’s memoranda, which appear (from the samples provided by that officious editor, Pottle) to be more pleasingly Pepys-ian, the journals provide a snap-shot of experiences and feelings with which it is impossible to argue. 3 One is consoled in face of the temptation to argue, however, by the recollection that he probably wouldn’t have listened anyway.

- I happened to read this passage shortly after that part in Pride and Prejudice where Charlotte Lucas decides to marry Mr. Collins. The chapter in Jill Heydt-Stevenson’s Austen’s Unbecoming Conjunctions: Subversive Laughter, Embodied History is particularly illuminating on the plight of such ‘unclean’ gentlewomen. I will make no substantial remark about Boswell’s plebeian philandering and his superficial understanding of recurrent venereal diseases: dirty linen indeed. I would like to note, however, that he gave two guineas as a loan/gift to a woman who became his mistress, although this meant he had to limit some of this expenditures until the date of his next allowance; in the meantime, he went around to booksellers to whom he had paid a deposit for borrowing privileges and reclaimed his deposits (a total of just over two guineas as I recall); when he found he had another dose of the clap (despite not performing concubinage [his term] with anyone else in the meantime), he sent his mistress packing – and sent a note ’round to reclaim the two guineas (which she returned a day or so later without comment).[↩]

- This was the case with Agamben, for example, which I tried to read, setting aside my annoyance at his constant reference only to ‘men’ or ‘man’ as actors in life’s drama – he’s just an old-fashioned fuddy-duddy, I thought, and uses the masculine in a general sense; then I encountered his first (and only) inclusion of women as actors (in Infancy and History) – as participants in pornography (though he politely, coyly includes the possibility of male-identifying participants as well) – and realized that, no, perhaps I could embrace the state of exception (I am misusing this phrase out of spite) and not bother with someone who succumbed to the habit of thinking in this way. This, though not entirely relevant here, is a minor rant I have been brooding on for quite some time; I felt Boswell deserved the opportunity to shine in comparison (although this goes in a footnote, because I am not quite sure he deserves to shine too much).[↩]

- Although one cannot quite wholly approve of everything he recounts: one feels sympathy when he is pranked by his friends, and one cringes slightly at his jocular letter to Hume.[↩]