August 2023

Too Much to Know

4 August 2023, around 8.21.

An examination that aims to incorporate intellectual history and material studies – and that may ultimately fall into the space between them (ah, yes, a gap in the literature). Focuses on works of reference (see chapter on genres) and how ‘scholars’ (how are they to be defined? how is a scholar different from an author? an amateur? is it necessary to distinguish? Probably not) in Early Modern Europe managed large amounts of information (i.e. on different slips of paper that are either copied or cut from their point of origin – see the chapters on note-taking and compilers). While there is a clear connection between the two topics, the book starts out by emphasizing the human element (behavior/culture), but switches midway through to center the works of reference (the data). Wide-ranging and intellectually rigorous, with an impressive bibliography, it is also clear in its presentation – and its limitations. An invaluable reference.

procedural

11 August 2023, around 4.37.

…only a particular concatenation of circumstances will reveal that one man always acts in a good way because his instinctual inclinations compel him to, and the other is good only in so far and for so long as such cultural behaviour is advantageous for his own selfish purposes. But superficial acquaintance with an individual will not enable us to distinguish between the two cases, and we are certainly misled by our optimism into grossly exaggerating the number of human beings who have been transformed in a cultural sense.

The other day I went to the courthouse for jury duty. The last time I had received a summons was in late 2020 and had gone to the courthouse and through the sepulchral security only to find that they had no need of jurors (with the not particularly subtle implication that this information had been posted on their website and it would have been more considerate of me to have checked there, rather than waste their time by coming in person – but time is to be wasted and has no better use, in my opinion). Message boards over the line for security, silent and blank the last time I was there, now broadcast determinedly solicitous messages from various courthouse staff, the knell of repeated words and phrases – ‘procedural justice’, ‘listen’, ‘rules’, ‘respect’ – providing no very happy vision for the day ahead, one almost as dismal as the overcast morning.

At the head of the stairs, a clerk collected compensation forms and handed out brightly colored badges, directing the jury pool to trickle into a large holding tank furnished with uncomfortable chairs in unsoothing shades of blue. The windows running along one wall barely broke above the trees to provide a view out over the river. I selected a chair behind a concrete pillar that effectively blocked my view of the front and, after admiring the minute fissures and sedimentation in said pillar, settled in to do some of my own work for the twenty minutes before the room was called to attention for training.

There is a comforting familiarity to entry-level training (here presented in video format, half PSA, half infomercial), the invalid-ish gruel of simple keywords – ‘evidence’, ‘duty’, ‘unconscious’, ‘bias’ – made almost palatable by repeated expressions of appreciation and thanks simply for showing up. By the time the videos were over, it was time for the regularly scheduled break, which ended only shortly before the regularly scheduled, ninety-minute lunch. A slow day, the clerk noted, before sending half the jurors home.

From my uncomfortable chair, I alternated between working and reading (The Death of Vazir-Mukhtar and Euthyphro), before finally being called as the second-to-last juror for a panel in the early afternoon. I took the elevator up with my unfamiliar peers to a bright, curiously empty hallway bounded by windows through which reflected sunlight sparkled off the river now that the morning clouds had cleared. We started down the hall as a court clerk rounded the corner, backlit and radiant as justice herself; actually, she said, we won’t be needing the last five jurors – you can go. So we went, unexpectedly free, out into the summer afternoon sun.

affected puppy

14 August 2023, around 4.17.

I have always observed that the most learned people, that is, those who have read the most Latin, write the worst; and that distinguishes the Latin of gentleman scholar from that of a pedant. A gentleman has, probably, read no other Latin than that of the Augustan age; and therefore can write no other, whereas the pedant has read much more bad Latin than good, and consequently writes so too. He looks upon the best classical books, as books for school-boys, and consequently below him; but pores over fragments of obscure authors, treasures up the obsolete words which he meets with there, and uses them upon all occasions to show his reading at the expense of his judgment. Plautus is his favorite author, not for the sake of the wit and the vis comica of his comedies, but upon account of the many obsolete words, and the cant of low characters, which are to be met with nowhere else. He will rather use olli than illi, optume than optima, and any bad word rather than any good one, provided he can but prove, that strictly speaking, it is Latin; that is, that it was written by a Roman. By this rule, I might now write to you in the language of Chaucer or Spenser, and assert that I wrote English, because it was English in their days; but I should be a most affected puppy if I did so, and you would not understand three words of my letter. All these, and such like affected peculiarities, are the characteristics of learned coxcombs and pedants, and are carefully avoided by all men of sense.

the rosy outlook

21 August 2023, around 10.07.

It is a nightmarish scene, yet one that seems to embody the conditions of a new dark age. Our vision is increasingly universal, but our agency is ever more reduced. We know more and more about the world, while being less and less able to do anything about it. The resulting sense of helplessness, rather than giving us pause to reconsider our assumptions, seems to be driving us deeper into paranoia and social disintegration under surveillance, more distrust, an ever-greater insistence on the power of images and computation to rectify a situation that is produced by our unquestioning belief in their authority.

- After describing the video taken by an automated home security camera activated by a wildfire destroying the home thus ‘protected’.[↩]

a new perplexion

24 August 2023, around 5.12.

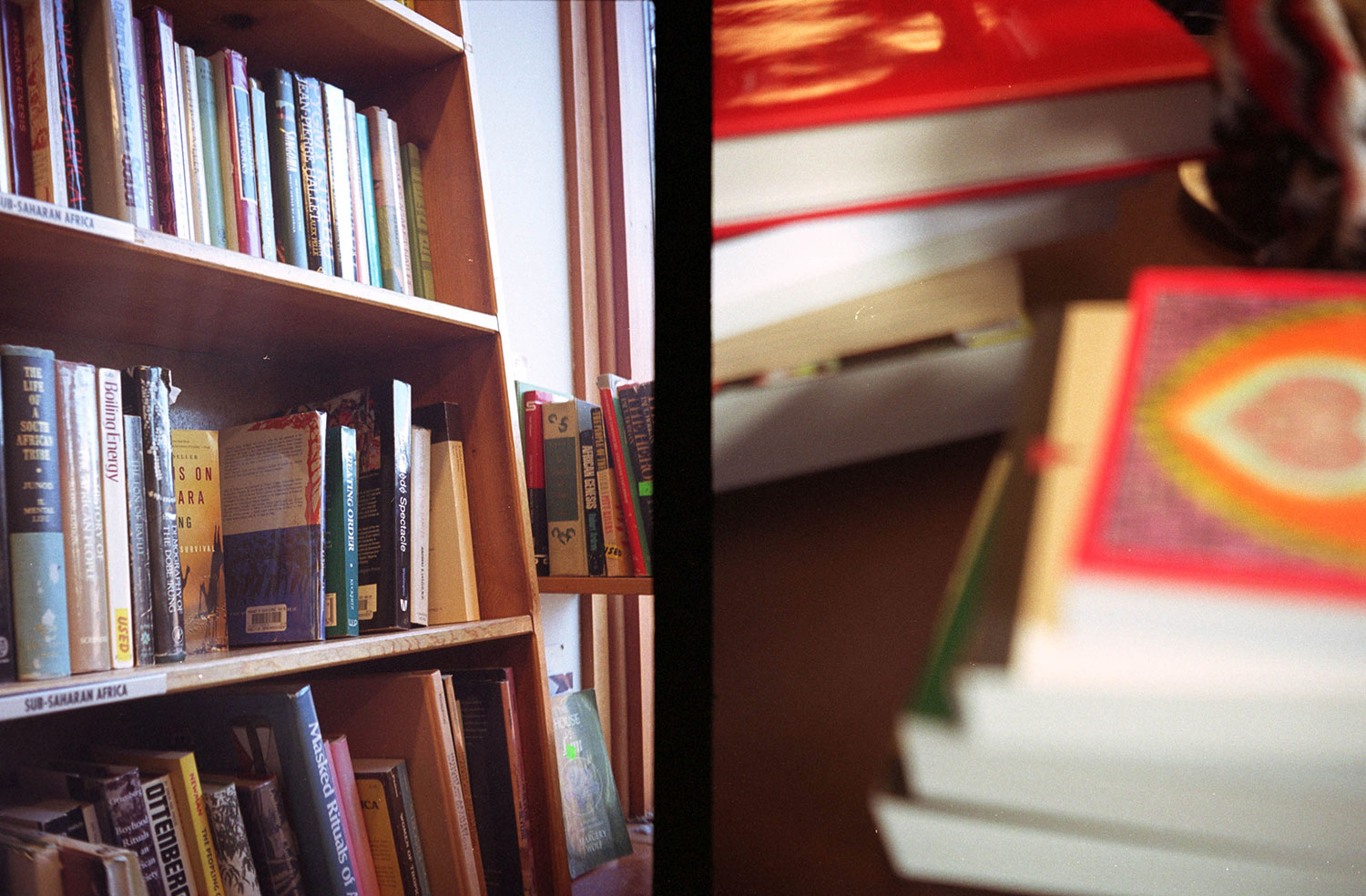

Some bookstores don’t change; one revisits them years later and everything is same, save for the accretion of additional detritus and the depredations of the occasional browser. Other bookstores seem to feel that if they are to last, they must change constantly: Sell puzzles instead of magazines, socks instead of – books, I suppose. It has been a gradual process, but long gaps between visits can make for startling metamorphoses. For instance: The corner of shelves that used to house classics (in the broad sense, from Gilgamesh to Genji) first suffered encroachment along its shorter flank from the Westerns and nautical tales; Sappho and Homer lost ground to Louis L’Amour and C.S. Forester. The classics fell back further as literature shrank and, with it, criticism: They crossed the aisle, taking space from the outpourings of the Shakespeare industry. The entire row of shelves where the classics used to be, from top to bottom, is now given over to the prizes of BookTok and paranormal romance, all jewel tones and wholesome lettering. 1 If one were expecting to find Thucydides and Horace, the contrast would be sharp: I write for all time, the man said, not to be heard and forgotten. 2

Herodotus is always up for a strange story, though, and one hardly needs to move Apuleius at all. 3

- One could pretend to be horrified, but that would be an unfortunate instance of insufferable preciosity.[↩]

- The bronze doodads (than which poems are more durable) are probably next to the socks.[↩]

- It is disorienting, though, as the Greek and Latin texts, which used to be shelved with the translations and criticism, have been whisked away to the foreign languages (and even there are dwindling away to a small cluster of Loebs).[↩]

the nerve

25 August 2023, around 12.28.

All our criticism consists of reproaching others with not having the qualities that we believe ourselves to have.

It also consists of reproaching others with having those qualities that we would like to have, but don’t.

Adversaria (5)

31 August 2023, around 4.33.

‘Take a story from a place and drop it into another place and it doesn’t necessarily make sense, at least not at first. Like people, stories don’t always travel well. Nothing belongs everywhere, and some things only belong somewhere. But some stories, when they travel, can spark strange things in unmeasured hearts’ —Paul Kingsnorth (Savage Gods, p. 31)

‘Why is it that destroying things is an activity to share with someone you love, while repairing things is done alone?’ —Akiko Busch (Everything Else Is Bric-a-Brac, ‘Damage’, 20%)

‘Sometimes, very briefly, a blank moment—a kind of numbness—which is not a moment of forgetfulness. This terrifies me’ —Roland Barthes (Mourning Diary, trans. Richard Howard, 31 October 1977)

‘It is, when all is said and done, when faced with the subject of death that we feel most bookish’ —Jules Renard (Journal, trans. Louise Bogan and Elizabeth Roget, December 1893)

‘We all think we have reason to reproach Nature and our destiny for congenital and infantile disadvantages; we all demand reparation for early wounds to our narcissism, our self-love. Why did not Nature give us the golden curls of Balder or the strength of Siegfried or the lofty brow of a genius or the noble profile of aristocracy? Why were we born in a middle-class home instead of in a royal palace? We could carry off beauty and distinction quite as well as any of those whom we are now obliged to envy for these qualities’ —Sigmund Freud (‘Some Character-Types Met With in Psycho-Analytic Work’, in Collected Works, vol. 14, p. 315)

‘What’s remarkable about these notes is a devastated subject being the victim of presence of mind’ —Roland Barthes (Mourning Diary, trans. Richard Howard, 2 November 1977)

‘…the way we attach value to things is both impossibly arbitrary and very, very precisely measured’ —Akiko Busch (Everything Else Is Bric-a-Brac, ‘Rewards’, 21%)

‘Sometimes, in a macabre imitation, I stop int eh middle of the road and open my mouth the way his was open on the bed. […] My laziness feeds on his death. My only inclination is to contemplate the picture that struck so terribly at my eyes.’ —Jules Renard (Journal, trans. Louise Bogan and Elizabeth Roget, July 1897)

‘Everything seemed normal. That’s what “normal” is for. It’s a word we use to paint over the cracks in what we fail to live with’ —Paul Kingsnorth (Savage Gods, p. 80)

‘Solitude = having no one at home to whom you can say: I’ll be back at a specific time or who you can call to say (or to whom you can just say): voilà. I’m home now’ —Roland Barthes (Mourning Diary, trans. Richard Howard, 11 November 1977)

‘We must of course guard against thinking of every event whose cause is unknown as “causeless.” This, as I have already stressed is admissible only when a cause is not even thinkable. But thinkability is itself an ida that needs the most rigorous criticism’ —C.G. Jung (Synchronicity, trans. R.F.C. Hull, p. 102 (¶967))

‘Chaotic, erratic: moments (of distress, of love of life) as fresh now as on the first day’ —Roland Barthes (Mourning Diary, trans. Richard Howard, 29 November 1977)

‘I thought I wanted to belong. I thought I needed to have a place, a people. But every time I find a place, I don’t fit into it. Something takes me away from it, from the campfire to the slopes o the mountain. Every time I could belong, I push it away. So I suppose this must be who I am. Or, this must be part of who I am, one faction, jostling with the others’ —Paul Kingsnorth (Savage Gods, p. 120)

‘…places exist in memory almost entirely differently than they exist in the material world.’ —Akiko Busch (Everything Else Is Bric-a-Brac, ‘Music’, 53%)

‘…it’s when we’re busy, distracted, sought out, exteriorized, that we suffer most. Inwardness, calm, solitude make us less miserable’ —Roland Barthes (Mourning Diary, trans. Richard Howard, 19 March 1978)

‘At Harvard he discovered, lying in idleness, a fund for the support of psychic research and he put it to work’ —J.B. Rhine (New Frontiers of the Mind)

‘Despite the fact that the statistical method is in general highly unsuited to do justice to unusual events, Rhine’s experiments have nevertheless withstood the ruinous influence of statistics. Their results must therefore be taken into account in any assessment of synchronistic phenomena’ —C.G. Jung (Synchronicity, trans. R.F.C. Hull, p. 64 (¶911))

‘How annoying to be in mourning! Every moment you must remind yourself that you are sad.’ —Jules Renard (Journal, trans. Louise Bogan and Elizabeth Roget, September 1897)

‘…by remembering it he had made the story his; and insofar as I have remembered it, it is mine; and now, if you like it, it’s yours. In the tale, in the telling, we are all one blood. Take the tale in your teeth, then, and bite till the blood runs, hoping it’s not poison; and we will all come to the end together, and even to the beginning: living, as we do, in the middle’ —Ursula K. Le Guin (Dancing at the Edge of the World, ‘It Was a Dark and Stormy Night; Or, Why Are We Huddling about the Campfire?’, p.30)