February 2024

beacon

1 February 2024, around 17.51.

For the composition and writing of this or my other works, I did not prepare a draft on the wax tablets, but committed them to the written page in their final form as I thought them out.

Even though it is vacation, one still wakes up at half past four, and in the quiet of the morning, one sits in the library at the small hotel, using the Salton Sea Atlas as a writing board for whatever scribbling one does in the morning. One settles into a daily walk along the beach after breakfast, usually in the wind and rain, but occasionally with a bit of sun. The rest of the day is spent reading or napping. It is very pleasant.

It is time, however, to return to town and pick up the strands of life that one has, for the moment, set down.

goals

2 February 2024, around 15.39.

…in browsing on these ancient words the pasture so rich for the philologist yields little grain for the student of literature, either in fruit of meaning or in beauty of sound. […] The origin of some of these strange growths is still obscure; but it seems as though devotees of some literary cult had used all their ingenuity to pick out from glossaries and recondite and mysterious sources a language of their own, foreign to the writing of their time.

dotty

3 February 2024, around 18.45.

So when I got through telling Dorothy what I thought up, Dorothy looked at me and looked at me and she really said she thought my brains were a miracle. I mean she said my brains reminded her of a radio because you listen to it for days and days and you get discouradged and just when you are getting ready to smash it, something comes out that is a masterpiece.

* * *

A pleasant lazy Saturday on which I finally finish reading a few books and for a walk to return two inter-library loans (which I managed to read before their due dates) on which I encounter a yard with aggressively whimsical lawn ornaments that would baffle the canons of taste, should said canons show up to dispute the matter. No other amusement in the offing, 1 I continue my stroll and complete my errands to leave the afternoon free for other idlenesses.

* * *

I mean sometimes Dorothy becomes Philosophical, and says something that really makes a girl wonder how anyone who can make such a Philosophical remark can waste her time like Dorothy does.

- Which, one discovers by the simple expedient of consulting a dictionary, is ‘[t]he part of the visible sea at a distance from the shore beyond anchorages or inshore navigational dangers’, along with other more figurative senses; thus have I broadened my horizons. I have not browsed in vain.[↩]

norming

4 February 2024, around 19.07.

Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, one cannot judge or admire this particular society by assuming that the language it speaks to itself is necessarily true.

I am in a book group or class (I suppose it’s a class, but it feels more like a book group) about the moral implications of bad behavior by artists. These vary, obviously. The group hasn’t really defined art, though, except in large, loosey-goosey terms that encompass everything from Finnegans Wake to finger-painting to a documentary on public access television, which has rather limited the course of the conversation. 1 Within its neatly defined structure, the conversation goes on well enough, though, and there is plenty to think about. Usually I end up with lines of poetry (that no one has quoted but memory has prompted) stuck in my head – ‘In luck or out the toil has left its mark: / That old perplexity an empty purse, / Or the day’s vanity, the night’s remorse’ or ‘If Napoleon if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if I told him if I told him if Napoleon’. Other books linger silently, living shades, at the edges of the conversation, but of course no conversation can contain everything.

All my life I have overheard, all my life I have listened to what people will let slip when they think you are part of their we. A we is so powerful. It is the most corrupt and formidable institution on earth. Its hands are full of the crispest and most persuasive currency. Its mouth is full of received, repeating language. The we closes its ranks to protect the space inside it, where the air is different. It does not protect people. It protects its own shape.

- Which, sure, fine. The only thing that has not been mentioned is ‘the sublime’, which makes me sad, because it seems relevant, but I am so poorly socialized I haven’t managed to think of a way to bring it up without seeming like a godawful twerp; I mentioned Plato once and it will take me several weeks to live it down.[↩]

cleanly

5 February 2024, around 12.48.

The hand that desires to cleanse the sores of other men must itself be clean, or the last state of the soul it touches may be worse than the first.

Perhaps part of the reason the class sticks with me, why I keep gnawing at the conversations in my mind, 1 is that terms are not defined.

If the artist is morally fallible (and who is not?), why should it be any worse than the failings of some less creative or notable person? Who is this ‘artist’ anyhow, and why the devil should anyone (apart from child protective service and maybe the IRS) care what they do? The ‘artist’ (as archetype) talked about by the group seems to be halfway between Jesus and Superman, saving the world morally, figuratively, and perhaps literally, but with a strong predilection for sexual violence and probably drug abuse – Apollonian and Dionysian mashed into an unspeakable gruel.

But couldn’t an artist just be some schmuck who makes stuff that isn’t really practical? 2

- Yes, dear, ruminating they call that.[↩]

- Prigs and poets alike get torn apart by maenads. Mobs are equal opportunity critics.[↩]

paronomasia

6 February 2024, around 9.04.

Sketch for a decorative panel, by Sir James Thornhill (ca. 1700)

Ideas improve. The meaning of words plays a part in that improvement. Plagiarism is necessary. Progress depends on it. It sticks close to an author’s phrasing, exploits his expressions, deletes a false idea, replaces it with the right one.

* * *

…Pun Lightning, that jolt of connection when the language turns itself inside out, when two words suddenly profess they’re related to each other, or wish to be married, or were in league all along.

conveniency

7 February 2024, around 10.19.

Drawing of the Apulian shepherd, Claude Lorrain (ca. 1657)

There are no public institutions for the education of women, and there is accordingly nothing useless, absurd, or fantastical, in the common course of their education. They are taught what their parents or guardians judge it necessary or useful for them to learn, and they are taught nothing else. Every part of their education tends evidently to some useful purpose; either to improve the natural attractions of their person, or to form their mind to reserve, to modesty, to chastity, and to economy; to render them both likely to became the mistresses of a family, and to behave properly when they have become such. In every part of her life, a woman feels some conveniency or advantage from every part of her education. It seldom happens that a man, in any part of his life, derives any conveniency or advantage from some of the most laborious and troublesome parts of his education.

going for broke

8 February 2024, around 11.57.

left (4:00 a.m.) to right (3:59 a.m.)

(blue is reading, green is sleep)

The less you eat, drink, buy books, go to the theatre or to balls, or to the public house, and the less you think, love, theorize, sing, paint, fence, etc., the more you save and the greater will become your treasure which neither moths nor maggots can consume – your capital.

biophagous

9 February 2024, around 17.26.

…soon memory pours forth from every direction, sprouting its vines and flowers up around you till the old garden’s taken shape in all its fragrant glory. Almost unbelievable how much can rush forward to fill an absolute blankness.

There are so many memoirs I’m in the middle of reading, or have just finished reading, or am just about to read, and they tell their tales of strange normalcy or ordinary absurdity in a keen and keening chorus, making sense of nonsense and vice versa. They blend together and untangle, their questions acute, oracular, unanswerable, and I cannot tell them apart, just as I cannot mistake one for another.

It is uneasy reading. The presence of a chorus makes one wonder where the hero has wandered off to and what unfortunate ending is creeping slowly, slowly toward the footlights of the present moment.

befogged

10 February 2024, around 17.37.

The mist is my subject. I am absent-minded, deeply interior and have a poor sense of direction. Life is punctuated by moments when I have no idea where I am or what’s in front of me. I can’t see. I can’t understand what’s being said or I can’t make sense. This is my ‘science’ and what I write about.

tracings

11 February 2024, around 13.33.

In the course of his travels, he generally acquires some knowledge of one or two foreign languages; a knowledge, however, which is seldom sufficient to enable him either to speak or write them with propriety. In other respects, he commonly returns home more conceited, more unprincipled, more dissipated, and more incapable of any serious application, either to study or to business, than he could well have become in so short a time had he lived at home. By travelling so very young, by spending in the most frivolous dissipation the most precious years of his life, at a distance from the inspection and control of his parents and relations, every useful habit, which the earlier parts of his education might have had some tendency to form in him, instead of being riveted and confirmed, is almost necessarily either weakened or effaced.

Although it presents itself as an examination of happiness and memory, structured by a loose examination of Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Traces is a study abroad memoir, which is an odd genre that, like the Peace Corps memoir, is problematic in its privilege, its promises, and the limitations of its scope. That does not mean it is not a charming or elegant book – and certainly there is the savor of sour grapes in the vinegar here – but it is a memoir of an (in)experience, rather than the summing up its tone suggests it might like to be. 1

- Like certain sorts of fish one encounters at fancy tables – too many bones, not enough meat.[↩]

back in the day

12 February 2024, around 15.29.

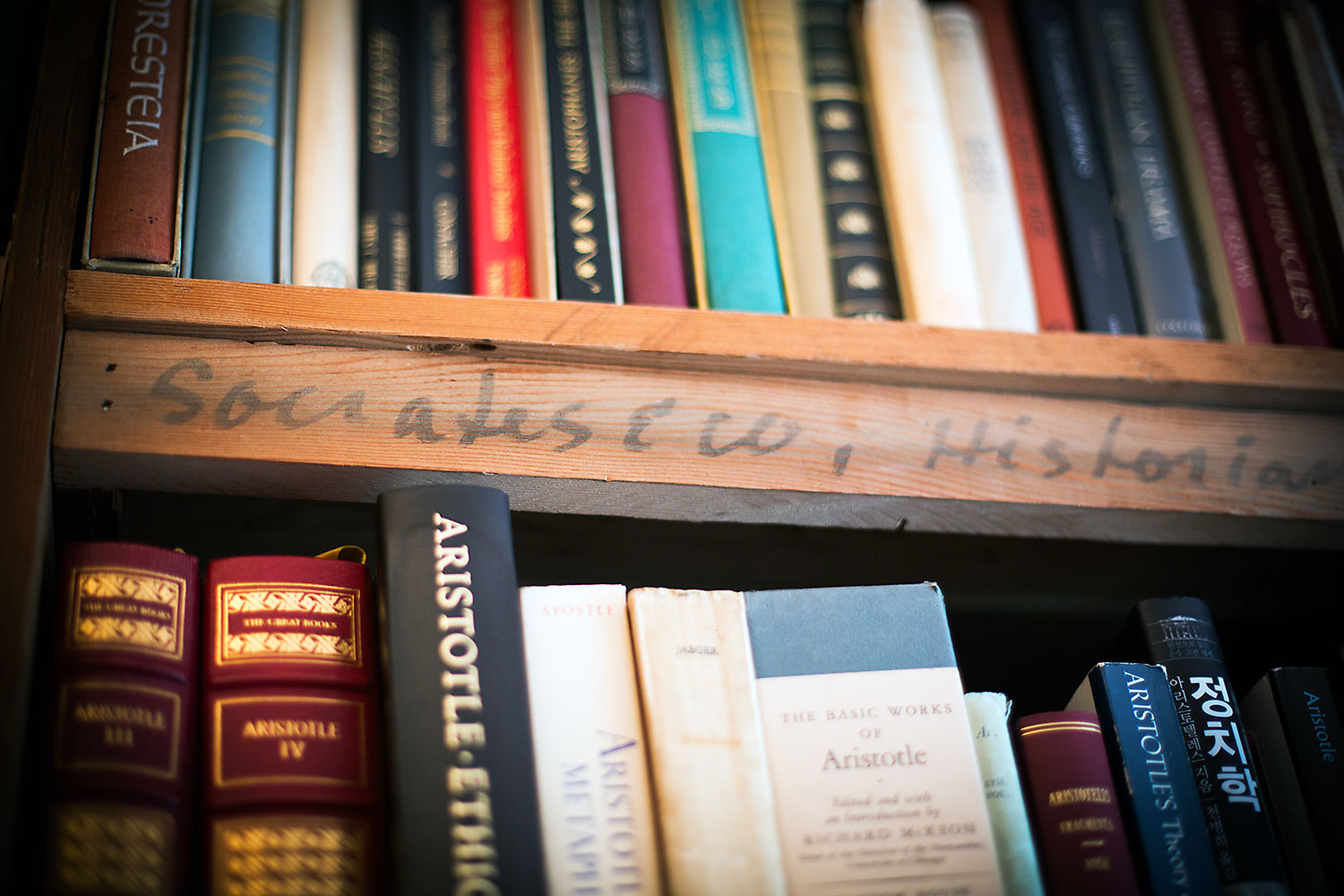

Socrates & co.

ticked off

13 February 2024, around 15.09.

I’m not quite certain how one could read only one book at time. I mean, obviously, at any moment, one is only reading one book at a time, without much confusion, but one’s moods and interests so seldom remain the same from the time one wakes up until the it’s time to put the light out that, unless someone is dictating one’s reading, it doesn’t seem right – it doesn’t seem fair to the book – to stick to only one work. Certainly having more than ten on the go at one time is excessive. One cannot give them enough of one’s attention, that mental caress of thought, wayward though it may be. So the books sit around in stacks, receiving more or less attention, and it is not certain whether books or reader are ticking off more items on any given list. It is rather dusty.

matutinal

14 February 2024, around 18.43.

This morning, the morning books were not working. They have grown in number, which is part of the problem. Really there should be only one morning book; perhaps two. The book should be both rigorous enough to require some attention (which helps one to wake up) but also interesting enough to provide a spark of alertness to carry over into the rest of the day. If there is more than one book, they should be quite different or, at the very least, distinct. For a while I had been successful with two or three morning books, particularly when two different translations of, say, Gilgamesh, were involved. Somehow, though, I have managed to get up to five. Two of them are perfect for their moment – I have no complaints about Wealth of Nations or Abigail Williams’s The Social Life of Books, which I might not attend to later in the day, but are perfect for morning reading.

The other three books, however, are driving me a bit batty, as the authorial voices are so strident and overpowering that rather than giving tone to the day, they deaden any mental acuity I might possess. This was truly a surprise in the case of a Kafka’s aphorisms, which, if I was not expecting to enjoy, I was at least hoping to find interesting. But they are scarcely aphorisms (although this comes of reading them immediately after finishing La Rochefoucauld, who provides very stereotypical aphorisms by the book), and the commentary, while illuminating, is also disheartening, as it provides a snapshot of the author as a person who, well, relished his self-defeating habits and nourished them like queasy distempered kittens. 1 A rather dismal way to start the day.

- My apologies to all kittens. And habits.[↩]

addendum

15 February 2024, around 11.20.

The more they are instructed, the less liable they are to the delusions of enthusiasm and superstition, which, among ignorant nations frequently occasion the most dreadful disorders. An instructed and intelligent people, besides, are always more decent and orderly than an ignorant and stupid one.

I am informed that I may have suggested Adam Smith lacks an authorial voice that could be described as strident or overpowering (or commanding in anyway). That is not the case. His tone – the imperturbable reasonableness, the sly irony, the unexpected humor – is one of his great attractions. Certainly he is not as openly funny as Marx nor so boldly bitter in his criticisms, but he can be just as acute and occasionally more cutting.

florilegium

16 February 2024, around 18.25.

Time is a wayward traveller, who sometimes rides post-haste through thick and thin, sometimes loiters on the road or falls asleep in the saddle, so that, fearing he is engulfed, we are half inclined to send with ropes and lanterns to drag him out of the deep miry ways: it is therefore not surprising if now and again the events of a century are crowded into the annals of one brief lifetime.

- As promising a beginning for a book on gardening as one could hope for; it is mentioned in passing in Cristina Campo’s The Unforgivable: And Other Writings, and I am glad I looked it up.[↩]

kavka

17 February 2024, around 10.39.

Die Krähen behaupten, eine einzige Krähe könnte den Himmel zerstören. Das ist zweifellos, beweist aber nichts gegen den Himmel, denn Himmel bedeutet eben: Unmöglichkeit von Krähen.

The crows claim that a single crow could destroy heaven. That is incontestable, but it offers no proof at all against heaven, because heaven does signify the impossibility of crows.

Yesterday evening a mass of crows flew overhead, dark angles against the clouds, which in the dusk were blue as though the sky were clear.

Citation (77)

18 February 2024, around 16.42.

I write in order to meet myself. I want to catch up with, to become, the person I once was and sometimes am and who has always been there – noting what I really think and feel, see and believe.

baggage

19 February 2024, around 8.49.

There is a bit in Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments that I misremembered, misunderstood, or made up entirely, but the gist of it was that if one takes on one of a thinker’s ideas, one has to take on their entire system of thinking and being – the faults in their logic and the faults in their life. 1 Agreeing with Aristotle’s definition of happiness or friendship, for example, would mean that one accepts his views on the (in)humanity of women or the appropriateness of slavery, or that one approved of his navigation of the admittedly tricky political situations he encountered. Even if one does not deliberately take hold of those aspects as handles for grasping a worldview, one is still picking them up and carrying them along with the elements one has deliberately chosen. They are inseparable.

I found this troubling. For a long time, liking Smith’s prose, I refused to read a biography of him, because I was afraid of the horrible things I might find. 2

- I could not find the passage in question when I looked for it, so a citation (should one exist) will have to wait until I can scrape together a few crumbs of time to reread it.[↩]

- An instance, perhaps, of ‘a natural shrinking from raising curtains and looking into unlighted corners’, as Henry James would put it.[↩]

avaritia

20 February 2024, around 15.13.

Out walking the dog (not because she asked for a walk, but because I wasn’t able to concentrate on work and had nothing better to do), I was trying to think of destinations for a longer walk (the real walk of the day, without the dog), and thought about going to the bookstore to get a copy of a book that I already have checked out from the library. It’s not the sort of book that one would refer to, and I don’t think that I would reread it, but I had a sort of hunger for a it, mostly because I wanted to look up a few page numbers, to put a few stray marks in the margin, to handle paper instead of staring at a screen. The dog did her business, though, and we went back inside, by which point I figured on taking the rest of the day off from walking.

viola

21 February 2024, around 13.40.

…But if subtleties and sophisms composed the greater part of the metaphysics or pneumatics of the schools, they composed the whole of this cobweb science of ontology, which was likewise sometimes called metaphysics.

Wherein consisted the happiness and perfection of a man, considered not only as an individual, but as the member of a family, of a state, and of the great society of mankind, was the object which the ancient moral philosophy proposed to investigate. In that philosophy, the duties of human life were treated of as subservient to the happiness and perfection of human life, But when moral, as well as natural philosophy, came to be taught only as subservient to theology, the duties of human life were treated of as chiefly subservient to the happiness of a life to come. In the ancient philosophy, the perfection of virtue was represented as necessarily productive, to the person who possessed it, of the most perfect happiness in this life. In the modern philosophy, it was frequently represented as generally, or rather as almost always, inconsistent with any degree of happiness in this life; and heaven was to be earned only by penance and mortification, by the austerities and abasement of a monk, not by the liberal, generous, and spirited conduct of a man. Casuistry, and an ascetic morality, made up, in most cases, the greater part of the moral philosophy of the schools. By far the most important of all the different branches of philosophy became in this manner by far the most corrupted.

de monstra demonstranda

22 February 2024, around 11.26.

The school of Criticism has made known in print its superiority to human feelings and the world, above which it sits enthroned in sublime solitude, with nothing but an occasional roar of sarcastic laughter from its Olympian lips.

In the morning, we’ve been reading aloud Robert Alter’s translation of Genesis, mostly for the notes, but occasionally for the language, which draws attention to the dissonances in the narratives in ways that the King James version, for example, doesn’t quite manage.

The other morning we were reading Chapter 22, in which Abraham is asked to sacrifice his son – his only son, his beloved son, Isaac (that God of his is prepared to be quite specific sometimes). The telling is compressed, terse, and the notes tease out a pathos in what is not said, as Abraham chops the wood, takes the fire, takes the knife, and takes his son out to the wilderness. There’s no messenger can make a mother laugh at that.

* * *

Il y a de méchantes qualités qui font de grands talents.

(Great talents are sometimes born of mischievous propensities.)

It is troubling when people one would like to admire or love (or at a minimum feel uncomplicated in one’s positive emotions toward) do things that do not align with one’s own (or society’s) moral standards. It is not something I like to think about, personally, 1 but books and people do come with this sort of baggage, so it nudges at the edge of my thinking – often when I least expect it.

That is what drew me to Claire Dederer’s book Monsters, which is in part an attempt to expand on her essay ‘What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?’. 2 The book is advertised as being – and will I think be treated by most readers (or non-readers) as though it were in fact – about how one copes, as an audience member, when good art is made by bad people. It certainly raises this question, but it is not a book of criticism or philosophy or a monograph in reception studies. One finds on reading it that it is a memoir – the latest entry in a homeopathic treatment for undiagnosed Hegelianism, involving yoga, sex, and (now) criticism – so it is perhaps to be expected that it does not do more than jostle the periphery of the question, brushing at it as though it were a fresh stain on a new white shirt. 3

* * *

My book editor once explained the appeal of memoir thus: ‘It’s cozy and voyeuristic.’ In other words, we want to know how other people live […] That’s part of the memoirist’s job, it’s true, but in order to defeat narcissism, a memoirist also has to reveal the more brutal realities of, well, there’s no nice way to say this, the heart. This is the real moral function of the memoir: to say the uncomfortable, even the unsavory truth of one’s inmost being, so the reader might recognize herself and feel less alone.

Do readers of memoir want to feel less alone? Is that why people read? Is everyone looking for a ‘satisfying little jolt of recognition’? While most memoirs tend to suffer from solipsism, in this inverse solipsism (as mentioned, there is a very bad case of Hegelianism here, reaching near clinical levels), the author does not exist until reflected in the other. The book, to twist a witticism, is Miranda’s rage at not seeing Caliban’s face in the glass, an envious glance at ‘mischiefs manifold and sorceries terrible’.

In Monsters, Dederer flirts with the eroticism of glamour and power, which I find generally distasteful (i.e., her fascination does not make this reader, at least, feel less alone), but which Dederer seems to enjoy and has examined (‘at a very high word count’) in her earlier memoirs and personal essays. One does not need a cigar and a therapist’s couch to link the interest in Woody Allen, say, to the shelves of books on the film-maker in her late father’s houseboat (Poser, ch. 12), or her fascinated gaze on Roman Polanski with her own anxieties about parenthood and her tangled emotions about her mother: ‘if I wrote only about assault and predators, I didn’t have to face myself’ (Love & Trouble, ch. 21). 5 She does not seem to come closer to facing herself in Monsters, either, and it is precisely this human element – a real look in the mirror, at the frustration of not being brilliant, of the inevitability of losing things or people one cares about, about having to face one’s own misjudgments – that might have provided the glimmer of greater meaning. 6

In aspiring to draw near the flame of genius, Dederer strikes a lot matches: there are sparks of insight, but no lasting illumination. By which I mean that the sections of the book do not fundamentally change one’s perception of the works discussed, which is what genius, what good criticism can, perhaps should, do. 7 After reading Anahid Nersessian’s explorations of Keats’s odes, for example, I won’t be able to read those poems the same way I could before; even if I don’t necessarily agree with her interpretations, they have still been changed. My views on Doris Lessing or Lolita are not altered Dederer’s views, nor has the basic level of (dis)interest I feel in these works been shifted.

* * *

We allow the genius to give in to his impulses; he is said to have demons.

θεὸς δὲ ἀνθρώπῳ οὐ μείγνυται, ἀλλὰ διὰ τούτου πᾶσά ἐστιν ἡ ὁμιλία καὶ ἡ διάλεκτος θεοῖς πρὸς ἀνθρώπους, καὶ ἐγρηγορόσι καὶ καθεύδουσι: καὶ ὁ μὲν περὶ τὰ τοιαῦτα σοφὸς δαιμόνιος ἀνήρ, ὁ δὲ ἄλλο τι σοφὸς ὢν ἢ περὶ τέχνας ἢ χειρουργίας τινὰς βάναυσος.

God with man does not mingle: but it is through the daimonion that all society and converse of men with gods and gods with men occur, both waking and asleep. Whosoever is wise in these affairs is a spiritual man; to be wise in other matters, as in common arts and crafts, is for the mechanical. 8

It’s a matter of interpretation, isn’t it, whether the artist is a Promethean hero, bringing a divine light to humanity, or just some person wise in their craft. The idea of heroes makes me twitchy – they tend to be uncomfortable company (Antigone would not make a fun member for your book club, for example – all that family drama – and Achilles would aways spend knit night complaining about his boss). I’m on the side of the mechanicals.

* * *

What can you do, then, if you are haunted by a daimon(ion) or some other imp of the perverse? If it calls you to make or think or do (or not do) things that those not so troubled, not so called, not so inspired cannot or will not understand or approve or accept? Only one course of action seems true, seems possible. What can you do?

You chop the wood, you gather your notes, you take up fire and pen. You climb the mountain. You sit at your desk. And, as the moment demands, you prepare to murder your darlings. 9

- Ethics as a whole can be a troublingly squishy subject.[↩]

- This is not a new question for Dederer. In her first memoir, Poser, it appears in her analysis of the guru in Mapp and Lucia, who ‘is revealed as a charlatan, and yet what he has to teach is valuable’ (ch. 10). It comes up again in her second memoir, Love & Trouble, with its ‘letters’ to Roman Polanski (ch. 7: ‘does a genius get let off the hook?’; ch. 22: ‘You, Roman Polanski, became my very own monster of sexuality, and I loathed you, at a very high word count’).[↩]

- One senses a failure of editorial courage here, which is particularly melancholy in light of Dederer’s reported conversation with her therapist about her desire to write an ‘ambitious’ book (p. 169); this book had ambitions, but it is not ambitious. Incidentally, I am amazed at the courage with which Dederer presents her conversations with her therapist and her agent and her editor, as she seems to take a willful joy in mis- or over-interpreting. The bullying vulnerability is exhausting to behold.[↩]

- Merely as an aside: If your book editor is explaining your genre to you, it might not be your genre – or maybe they shouldn’t be your editor.[↩]

- The quote ends ‘…as a sexual person’, but the spirit is much the same.[↩]

- This is the frustration of reading memoir: one wants blood.[↩]

- Dederer discusses this strikingly – what she terms the ‘bossiness’ of genius – in the first of ‘letters’ to Polanski in Love & Trouble[↩]

- Jowett translates the last bit as: ‘The wisdom which understands this is spiritual; all other wisdom, such as that of arts and handicrafts, is mean and vulgar’, which is doubtless prettier English, but is a bit further away from the original meaning.[↩]

- The writing of this post has been strong influenced by PF’s summaries of Hegel and Kierkegaard’s interpretation of the Abraham/Isaac story, as well as the discussions from the 2024 Delve seminar on Dederer’s Monsters. It is written in the spirit of one of the assistants to the assistant page to the knight of really quite finite resignation.[↩]

counterfeit

23 February 2024, around 7.56.

Ein Umschwung. Lauernd, ängstlich, hoffend umschleicht die Antwort die Frage, sucht verzweifelt in ihrem unzugänglichen Gesicht, folgt ihr auf den sinnlosesten, d. h. von der Antwort möglichst webstrebenden Wegen.

A swerve. Lurking, skittish, hopeful, the answer prowls around the question, peers desperately into its unapproachable face, follows it on the most senseless paths, that is, those that veer as far away as possible from the answer.

The problem with Kafka’s ‘aphorisms’ is that they are not really aphorisms. It would be one thing if one could say that they were gnomic utterances or oracular dicta, but even that would be pointing in the wrong direction. They remind me most of affirmations, such as one might scribble on a sticky note and apply to the interior of one’s closet door or above one’s desk. Of course, because they are Kafka’s, they are not of the ‘I am strong’, ‘I am worthwhile’, ‘Live, laugh, love’ school; ‘negations’ might be a better term, but even that clings too close to the sunlit world.

the hazy reader

24 February 2024, around 17.35.

These little puzzles which, without exception, have an artistic purpose, should also be fun. The approximate reader, drowsy from the airliner’s unhealthy air and the complimentary drinks he has downed, always has the lamentable option of skipping, as he often did with the best-selling Lolita.

unsettlement

25 February 2024, around 16.54.

It is the uneasy time of year, when the weather is strange; one wakes up already tired to face the prospect of dragging oneself through the day. One looks at one’s stacks of books or tasks with hope for the morrow, but each day when it arrives carries plans away in an unwholesome deluge of idle nothings.

Perhaps tomorrow will be better.

lability

26 February 2024, around 14.17.

It is surely now time that our rulers should either realize this golden dream, in which they have been indulging themselves, perhaps, as well as the people; or that they should awake from it themselves, and endeavour to awaken the people. If the project cannot be completed, it ought to be given up.

aide-memoire

27 February 2024, around 11.50.

It is cold again today, and going out for my run felt burdensome, although I managed it, mostly by distracting myself by trying to sort out different genres of memoir. Some people say there are seven, others say there are thirteen, but none of their lists fully encompass the sub-generic specificities that I have drawn my attention, such as the creative mum club (Deborah Levy, Lavinia Greenlaw, et al.), the broken by their parents club (Gibbon, John Stuart Mill, Trollope, et al.), the poorly Irish ladies (which is a phrase I do not like but cannot get out of my head; A Ghost in the Throat, Constellations, etc.), the mental illness as defining characteristic (no names), the has not done or experienced anything worth writing a memoir about but writes decent prose and has no other ideas for a book and so succumbs to the solecism of solipsism club (no names), among others.

It is cold enough that I have turned on the electric heater that sits in the fireplace and warms the brick surround slightly, but not enough for comfort. The dog seems to find it cozy enough, judging by her snoring.

a common place

28 February 2024, around 17.25.

Adversaria (11)

29 February 2024, around 4.00.

‘…poetry, which is like modern dance for uncoordinated people’ —Claire Dederer (Love & Trouble, ch. 13)

‘…The Editor, an avuncular but testy figure who might send a few encouraging words written in a discouraging hand’ —Lavinia Greenlaw (Some Answers Without Questions, p. 99)

‘I read the letters but couldn’t understand them. I could understand the words but not the letters, yet I was trying to understand in order to get over my not-caring but the not-caring was stopping me from understanding, understanding without caring is not truly understanding, and faking understanding is not understanding’ —Noémi Lefebvre (Blue Self-Portrait, trans. Sophie Lewis, p. 57)

‘…we are all a patchwork of oddities’ —Anna Vaught (The Alchemy, p. 25)

‘The bookshelves went up up up ten feet, and then there was another expanse of ceiling above that, filled with dust motes drifting like the stuff of thought itself. It was as if the books were dreaming, and their dreams floated into the air above, just barely visible’ —Claire Dederer (Poser, ch. 5)

« La promptitude à croire le mal sans l’avoir assez examiné est un effet de l’orgueil et de la paresse. On veut trouver des coupables; et on ne veut pas se donner la peine d’examiner les crimes » —François duc de La Rochefoucauld (Les Maximes, 267)

‘…a healthy person had to watch himself continuously, he had to subject himself to minute rules, he had to guard against any deviation from the prescribed regimen. Only thus could he be healthy and live long, he was told. An odd way of achieving health and longevity!’ —Ludwig Edelstein (‘Ancient Philosophy and Medicine’ in Ancient, trans. C. Lilian Temkin, p. 358)

‘As long as necessity is socially dreamed, dreaming will remain necessary. The spectacle is the bad dream of a modern society in chains and ultimately expresses nothing more than its wish for sleep. The spectacle is the guardian of that sleep’ —Guy Debord (The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb, §21)

« Il arrive quelquefois des accidents dans la vie, d’où il faut être un peu fou pour se bien tirer. » —François duc de La Rochefoucauld (Les Maximes, 267)

Movable property ‘discountenances his reminiscences, his poetry and his enthusiastic gushings by historical and sarcastic recital of the baseness, cruelty, degradation, prostitution, infamy, anarch and revolt forged in the workshops of his romantic castles’ —Marx (‘Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts’, trans. Gregor Benton, in Early Writings, p. 339)

‘Books were there to be the same; to be ordered; to present life as a manageable, dependable proposition. Books were my stable family’ —Claire Dederer (Poser, ch. 12)

‘The desire to describe voice, gesture, skin color, is a desire to eat, take over, make into part of the pattern. I am happy every time to see a writer fail at this. I am happy every time to see real personhood resist our tricks. I am happy to see bodies insist that they are not shut up in this book, they are elsewhere. The tomb is empty, rejoice, he is not here.’ —Patricia Lockwood (Priestdaddy, p. 297

« Il arrive quelquefois des accidents dans la vie, d’où il faut être un peu fou pour se bien tirer. » —François duc de La Rochefoucauld (Les Maximes, 267)

‘When art, which was the common language of social inaction, develops into independent art in the modern sense, emerging from its original religious universe and becoming individual production of separate works, it too becomes subject to the movement governing the history of all separate culture. Its declaration of independence is the beginning of its end.’—Guy Debord (The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb, §186)

‘I am in the house of nouns here, and it fills me with the conviction that good books sometimes give: that life can be holdable in the hand, examined down to the dog hairs, eaten with the eyes and understood’ —Patricia Lockwood (Priestdaddy, p. 306)