June 2024

fundamentals

7 June 2024, around 7.30.

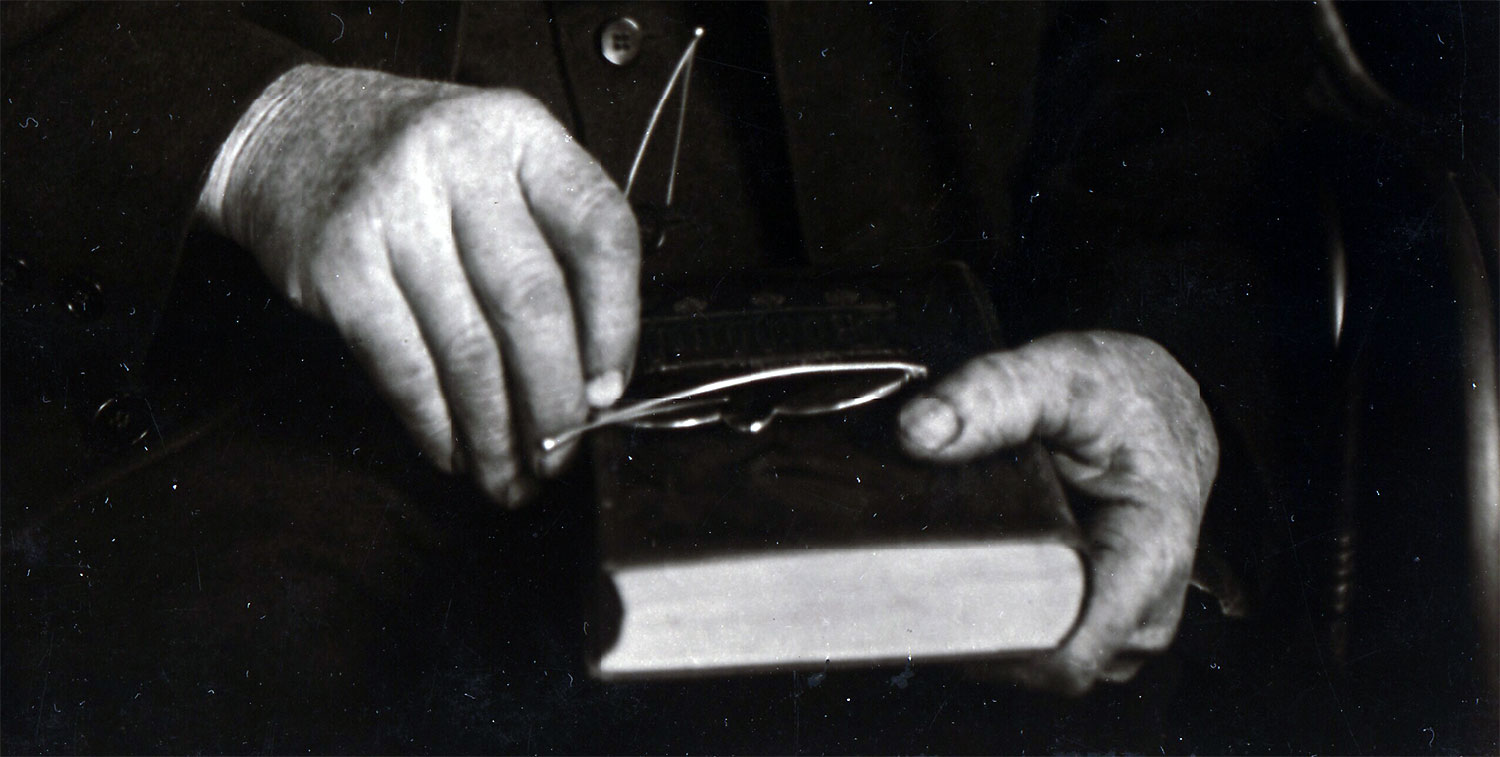

August Sander, Farmer (ca. 1925)

Let us say that what separates the great book from the merely good (or interesting) is that a great book, however it innovates, whatever its oddities, will teach the reader how it is to be read. 1 Grundrisse is not, then, a great book, but it is still in an interesting one in that it teaches the reader not how to read it (perhaps because, as a collection of notebooks, it is not really meant to be read) but rather how Marx was in the habit of reading. One senses the thread of a thought being untangled – but it is not being untangled on the page, but rather through it.

I will note that I am a very lazy reader of Marx and do not apply much living labor to his interpretation; it is perhaps no surprise that, of his writings, I find his journalism the most appealing, although the cute nicknames for and sarcasm directed at the authors criticized – particularly Ricardo, Malthus, Say, and Proudhon – make Grundrisse a close second and certainly superior (as a reading experience) to the early economic and philosophical manuscripts.

- This is in reference to books that might have a claim to greatness; a textbook teaches one (hopefully) how to read it, but that seldom makes it great qua book.[↩]

Citation (78)

10 June 2024, around 4.10.

Un historien a bien des devoirs. Permettez-moi de vous en rappeler ici deux qui sont de quelque considération, celui de ne point calomnier, et celui de ne point ennuyer. Je peux vous pardonner le premier, parce que votre ouvrage sera peu lu ; mais je ne puis vous pardonner le second, parce que j’ai été obligé de vous lire.

The duties of an historian are many and various. Allow me to remind you of two of them, which are of some consequence; these are, never to slander, and never to be tedious. For the first I can easily excuse you, because your book will be the less read; but for the last I cannot possibly forgive you, because I have been obliged to read it.

- Originally seen in Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, p. 223.[↩]

disjointed

19 June 2024, around 4.08.

…this element itself is neither living nor dead, present nor absent: it spectralizes. It does not belong to ontology, to the discourse on the Being of beings, or to the essence of life or death. It requires, then, what we call, to save time and space rather than just to make up a word, hauntology. We will take this category to be irreducible, and first of all to everything it makes possible: ontology, theology, positive or negative onto-theology.

All of the pipes are being replaced in the building, which is over a hundred years old and starting to show its age in various small (and large) ways, the decrepitude of the plumbing being one of the more insistent. We are staying away for the duration – or for more or less the duration – mostly to keep the dog happy. The clouds turn pearly at daybreak before the rain begins again. 2

- A bit too whimsical for my taste, a riffling and riffing through the pages of others rather than what could be called thinking.[↩]

- I had wanted to think about caretaking, about the necessity of stewardship toward the building, an acknowledgement of mere tenancy before handing things along to the future (as justification for inconvenience and uncertainty), but the dog wants to play outside and that somehow seems more important.[↩]

Adversaria (15)

30 June 2024, around 4.16.

‘To fail in everything, it is true, will always remain possible. Nothing will ever give us any insurance against this risk, still less against this feeling’ —Derrida (Specters of Marx, trans. Peggy Kamuf, p. 19)

‘He is constantly rediscovered and as constantly laid aside. He remains unreadable and unread’ —Isaiah Berlin (‘Vico: Philosophical Ideas’ in Three Critics of the Enlightenment, p. 146)

‘…what we are saying here will not please anyone. But who ever said that someone ever had to speak, think, or write in order to please someone else?’ —Derrida (Specters of Marx, trans. Peggy Kamuf, p. 109)

Words are counters, he says, echoing Hobbes unconsciously; language is a currency: men of genius can use it, but officials turn it, as they turn everything, into a sterile dogmatism, which they proceed to offer for their own and popular worship. This turns human relations into mechanical ones, and makes of what were living truths or a spontaneous capacity for acting in some appropriate fashion, a dead rule, an object for idolatrous worship. This is a sermon against dehumanisation and reification before those terms had been thought of.