the idleness ethic

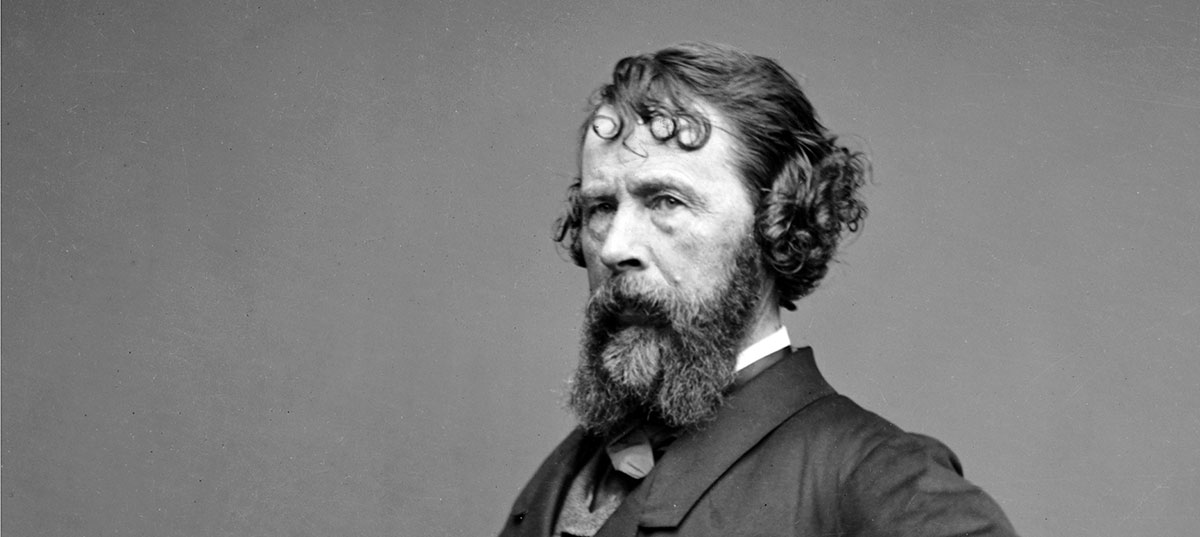

Nathaniel Parker Willis, photographed by Matthew Brady (ca. 1850s)

…the smell of earth and flowers coming to my nostrils once more, I begin to feel an interest in several who have sailed with me. Humanity, killed in me invariably by salt water, revives, I think, with this breath of hawthorn.

It’s a curious thing, agreeability. I did not think too much about it when I chose ‘the agreeable eye’ to represent, in a small way, the nature of this site, just as I did not think too much when naming it, but picked a word that seemed to me agreeable out of what I had recently read. The image, anyhow, is from a late nineteenth-century handbook of physiognomy, and was one of the few images that looked anatomically possible. In perusing the text some time later, I found that the ‘agreeable eye’ belonged to one N.P. Willis, 2 pictured above (looking much less agreeable, but with rather more facial hair). 3

Editors have a very sublime way of lumping Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, and under the diminished monosyllable of ‘the world,’ spanning it with their reflections as they would shade an ant-hill with an umbrella.

For all that he was one of the highest paid magazine writers in America in the 1840s, Willis appears to have been a dull dog, prose-wise, notable for ‘a shocking mixture of gossip, celebrity expose, and autobiographical confession.’ 4 Born to a family of publishers, possessed of an amiable, rather dandyish persona, 5 Willis worked for a variety of publications (as editor or author), was loosely associated with the Knickerbocker Group, and founded what later became Town & Country. 6 Although first known for his poetry, such fame as he had rested on his ability to present culture as an alienable good, which one could get at second-hand, just as good, but at a much lower price. 7 He took an unsentimental view of literary work, and noted he was ‘obliged to turn to account every trumpery thought I can lay my wits to. My rubbish, such as it is, brings me a very high price.’ 8 It would be safe to say that, in the annals of U.S. literary history, he is ‘a footnote to someone else’s story’ 9 – or, at the very least, three someones: his sister, Fanny Fern; 10 his servant, Harriet Jacobs; 11 and his protégé, Edgar Allan Poe. 12

What most surprises me in the past, is, that I ever should have confined my free soul and body, in the very narrow places and usages I have known in towns. I can only assimilate myself to a squirrel, brought up in a school-boy’s pocket, and let out some June morning on a snake fence.

If you have troubled your way through the footnotes, you will have gathered that N.P. Willis was not a particularly laudable character. Such virtues and vices as he may have possessed seem to have been of the passive sort, though: generally a matter of omission rather than viciousness. Indeed, he seems to have been, well, simply agreeable – even when it might have been better, more prudent, more just to disagree. In any case, he has been forgotten, save by those looking to write articles on the author as celebrity in nineteenth-century America or those who happen to flip through an old handbook of physiognomy. 13

- These quotations gathered rather by sortes than study.[↩]

- Poe, writing in 1846, notes of Willis that ‘Neither his nose nor his forehead can be defended; the latter would puzzle phrenology.’[↩]

- It is not a surprise that he looks so irritable in Brady’s portrait: in poor health, he had already outlived his fame and was embroiled in scandal and in quarreling with his sister.[↩]

- Mary Chapman, ‘Performing Culture,’ p. 153; plus ça change…[↩]

- In a private letter to literary agent James Lawson, Willis Gaylord Clark (a minor poet and twin brother of Lewis Gaylord Clark, editor of The Knickerbocker magazine) went so far as to call N.P. Willis ‘an impersonal passive verb – a pronoun of the feminine gender’; quoted in Kenneth Silverman, Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), p. 223.[↩]

- From privilege himself, he catered to the aspirations of others; if this particular case is of interest, see the essay by Maura D’Amore.[↩]

- This more or less cribbed from two articles by Sandra Tomc.[↩]

- Quoted in Silverman, p. 224 (or so – I started this post in 2016 and have long since returned the library book).[↩]

- Thomas N. Baker, Sentiment and Celebrity: Nathaniel Parker Willis and the Trials of Literary Fame (Oxford: OUP, 1999), p. 4.[↩]

- Fanny Fern, née Sarah Willis, provides an unflattering view of her brother in Ruth Hall, her work of ‘autofiction’ (as the kids on Twitter are calling it these days).[↩]

- I hope to consider Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, at greater length some other time; it will be sufficient to say that Jacobs wrote her memoir in the evenings while working as nanny at Idlewild, Willis’s estate, and Willis himself appears as the Southern-sympathizing Mr. Bruce. The character is, as one would guess, something of a moral non-entity; more attention is paid to his wives.[↩]

- Willis provided Poe with a literary platform, and indulged some of the poet’s more peculiar attempts at publicity. See, e.g., Silverman, p. 250f., or the essay by Richard Benton.[↩]

- Part of me wanted to spend this final paragraph in self-reflection, but the occupation did not prove agreeable.[↩]