ghost pain

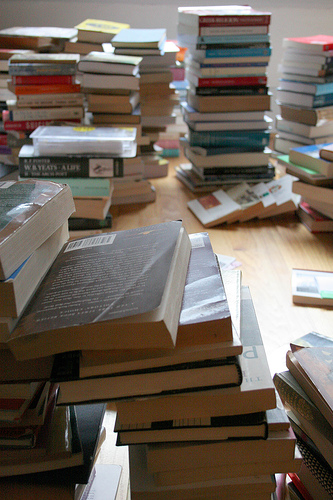

My bookshelves look like a fighter’s mouth, full of painful and surprising gaps. Even books I thought I could not do without, books that shaped my taste and who I am, are gone.

Let me explain. When we decided to move abroad I knew, of course, that most 1 of the books would have to be sold. Part of the excitement of travel is its weightlessness – It is difficult to move quickly with two thousand pounds of books. Three boxes in storage, two smaller boxes to ship, and a small handful for transit is not much better, but it is (ahem) a step in the right direction.

We’re not leaving for another year, but it’s as well to start now. We list them on the usual on-line outlet or we schlep them to Powell’s where we are offered ridiculously low prices for the growth of our personality and the development of our intellect. 2 Sometimes, indeed, nothing is offered, and our hopes and dreams – foxed and tattered and broken-spined – limp to the library to circulate, disintigrate, or be sold for a pittance & the public good.

It would be easier, and perhaps even more cost effective, to just ask the buyers from Powells to come and give us an offer on the lot. We would save on shipping, save on time; but I would lose out on something else: the chance to redefine my relationship to books.

They are my castle, my fortress, my comfort, my joy; they are my past, my present, my future; they are my mask. Because I would like to be the sort of person who takes down Hegel for a little light reading in the evening, or who needs to refer to two different editions of Homer in Greek on a daily basis. I am not that person; one edition will do. 3 It’s an idea that takes getting used to.

Of course I do try to look on the bright side: it’s a chance to start a whole new collection. Or it’s a chance not to, which might be better.

- The flesh is willing, but the spirit is weak.[↩]

- Even allowing for fond exaggeration, that’s partially a pleasant fiction. Assuming that books could stand for their contents, it would only have the slightest kernel of truth if the editions we had were the copies we originally read, which in many, perhaps most, cases they are not. I first read Shirley, for instance, as a small hardcover blue Oxford Classic, checked out from a college library; the edition I currently own is a Penguin. And really, who would lament a penguin?[↩]

- Down to the sentence level, down to a word-by-word basis it’s difficult to let go; because really, sadly, truly I don’t need or refer even to one.[↩]