a new perplexion

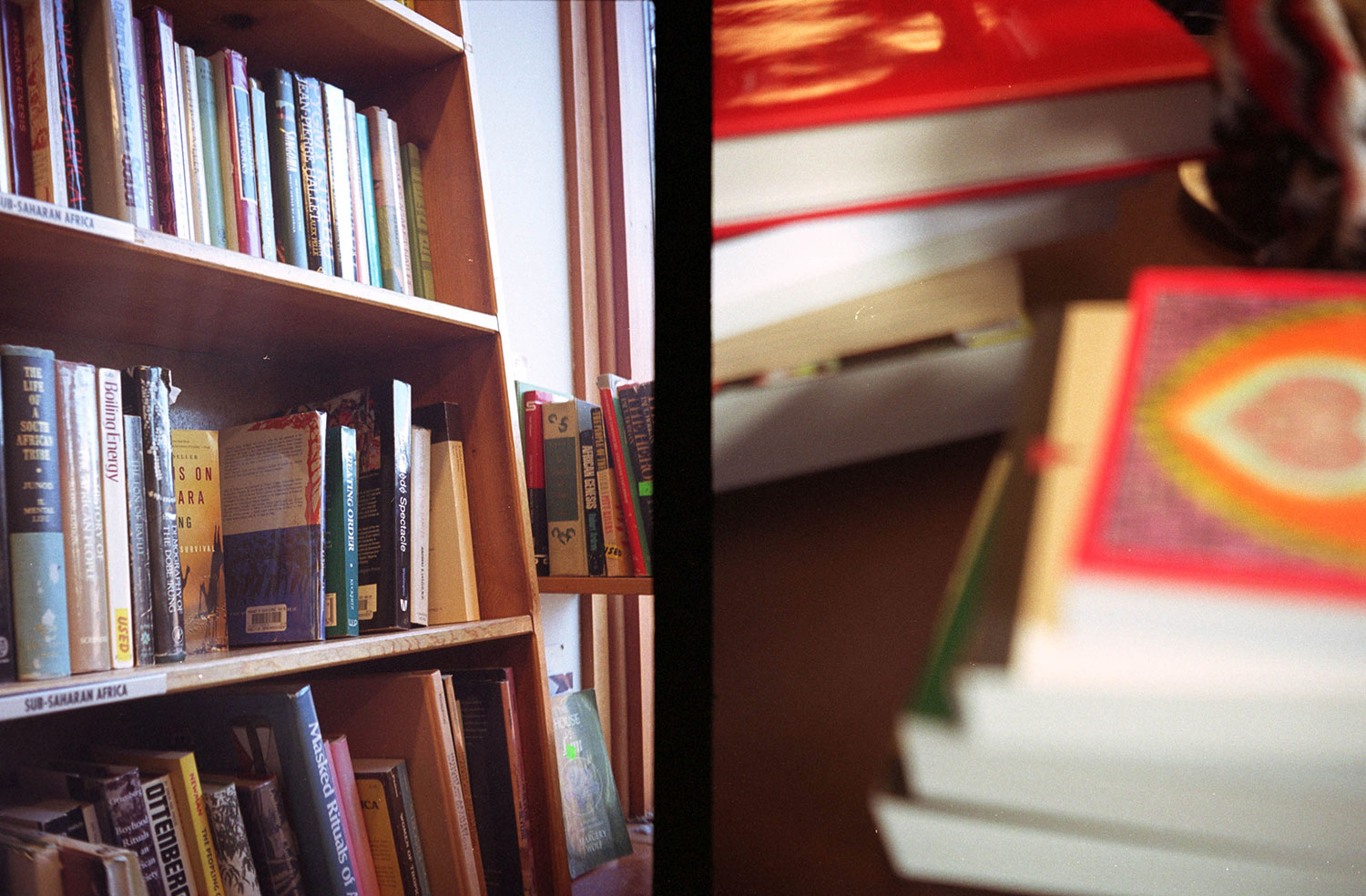

Some bookstores don’t change; one revisits them years later and everything is same, save for the accretion of additional detritus and the depredations of the occasional browser. Other bookstores seem to feel that if they are to last, they must change constantly: Sell puzzles instead of magazines, socks instead of – books, I suppose. It has been a gradual process, but long gaps between visits can make for startling metamorphoses. For instance: The corner of shelves that used to house classics (in the broad sense, from Gilgamesh to Genji) first suffered encroachment along its shorter flank from the Westerns and nautical tales; Sappho and Homer lost ground to Louis L’Amour and C.S. Forester. The classics fell back further as literature shrank and, with it, criticism: They crossed the aisle, taking space from the outpourings of the Shakespeare industry. The entire row of shelves where the classics used to be, from top to bottom, is now given over to the prizes of BookTok and paranormal romance, all jewel tones and wholesome lettering. 1 If one were expecting to find Thucydides and Horace, the contrast would be sharp: I write for all time, the man said, not to be heard and forgotten. 2

Herodotus is always up for a strange story, though, and one hardly needs to move Apuleius at all. 3

- One could pretend to be horrified, but that would be an unfortunate instance of insufferable preciosity.[↩]

- The bronze doodads (than which poems are more durable) are probably next to the socks.[↩]

- It is disorienting, though, as the Greek and Latin texts, which used to be shelved with the translations and criticism, have been whisked away to the foreign languages (and even there are dwindling away to a small cluster of Loebs).[↩]