exaltée

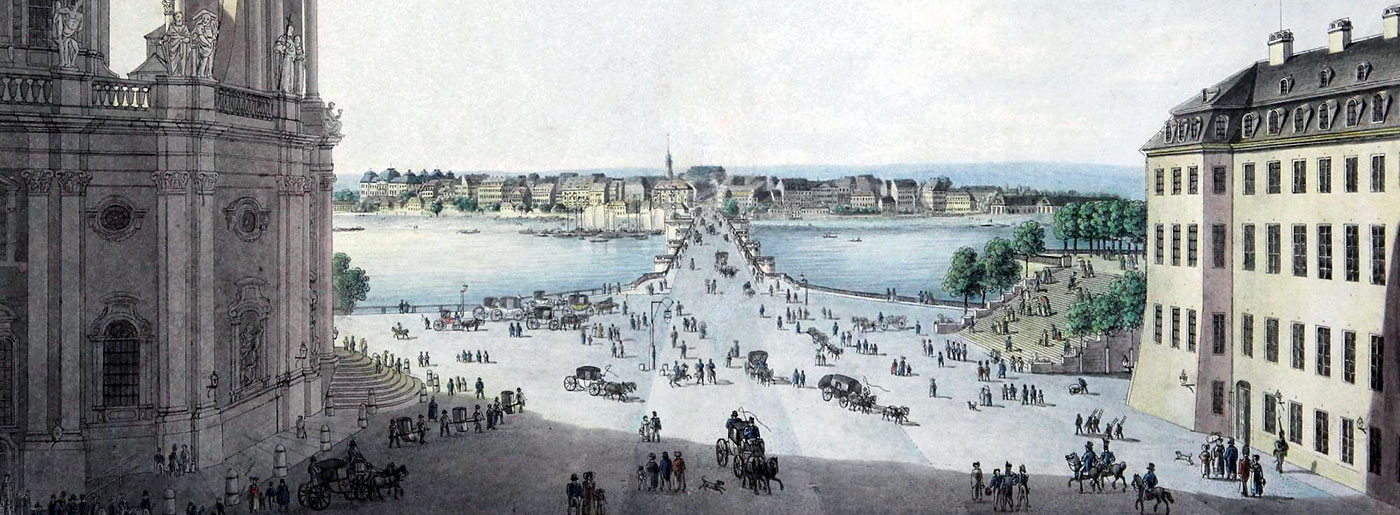

A view of a bridge, in watercolor, ca. 1820.

All recollections are like shadows, & all shadows are dark, be the objects that cause them ever so bright.

It is always a little strange to read published journals or diaries. The ones that I’ve encountered – Virginia Woolf’s, Pepys’, Dorothy Wordsworth’s – combine personal charm with a strong sense of being useful: behold, here is reference material. It is an odd combination, the frisson felt in access to a private mind (emotions present or visible beneath the surface) and the mundane, busybody curiosity about who in the household was responsible for ironing the handkerchiefs.

The journals of Emily Foster (written during her family’s residence in Dresden from 1821 to 1823) were published because of Washington Irving’s ‘warm attachment’ for the then eighteen year old, but the writer doesn’t appear until the last quarter of the volume and even then remains a very minor character. Indeed, the only novel information the journal seems to communicate about Irving is that he wore, for a short period, ill-advised mustachios (of which, thank heavens, no visual record remains). 1 I suppose it also confirms Irving’s predilection for emotionally unavailable females, but even as someone with no knowledge whatsoever about his biography, this hardly seems like news.

A view of Schloss Übigau, the Fosters’ first residence in Dresden, ca. 1830.

The editors did not trouble themselves to delve deeply into the history of Miss Foster, so their notes are incongruous, perfunctory, and patronizing – footnotes on what they considered to be a footnote. Despite the editors’ grudging consultation of Das alte Dresden, Foster’s journal does not cast much light on the city or its society, even considering the limitations of an expatriate’s view. 2 Few of the public performances are cross-referenced (and then only with Irving’s journals) and no overview of local taste in theatre or opera is given. Even the identity of the young man with whom Miss Foster seems to have been infatuated (and with whom she collaborated on at least the beginnings of an epistolary novel, read aloud in the evenings) is set aside to be considered in an article at a later date. 3

Educational practices are not given much attention either, which is unfortunate as this might have shed light on the journal’s purpose – perhaps for practicing freeform composition. 4 Many passages are in French, Italian, and German, and although the editors are snide about the schoolgirl mistakes, are not such mistakes permissible (or expected) in school exercises? The other children in the house (at least one other girl, Flora, and several boys, one of whom died during the period covered) also kept journals; on one occasion Miss Foster even suggests referring to her brother’s journal entries for additional details and amusing anecdotes about their travels. 5 This rather makes it seem as though the journal was an assigned task, rather than an outpouring of adolescent fervor (although of course the two are not mutually exclusive). One is left wondering about the purpose of the book, as published. It is frustrating, seeing so many paths for inquiry ignored – tho’ of course I am not following up on any of them, either. Perhaps the encounter must, after all, suffice.

- Its usefulness for the Irving devotee is therefore rather limited. I will confess that I have no great interest in Irving – ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ gave me nightmares as a child, which I still have not forgiven.[↩]

- ‘Expatriate’ is here used advisedly, as the Foster family’s residence abroad was not intended to be permanent.[↩]

- I am perhaps being harsher than the editors deserve, but I am having difficulty forgiving the decision to set the text of the journal in italic; it may have made it look more like ‘handwriting’, but it also makes it seem mincing and precious, which given the shrewdness of Foster’s observations and the seriousness of a young woman’s career (at least to herself) seems unnecessarily condescending.[↩]

- I was reminded of the French compositions both young female characters trouble themselves with in Shirley.[↩]

- Miss Foster also claims that she would be willing for anyone to read her journal, as written, without emendation – a bold claim for a type of document one is used to thinking of as private.[↩]